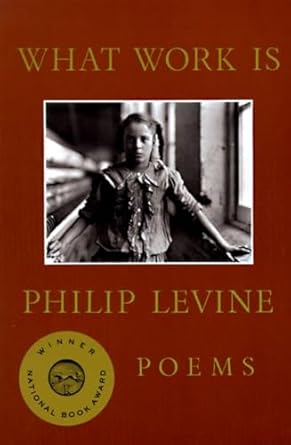

Philip Levine has died. That is the simple—the brutal—truth. I first encountered his work in the pages of a red anthology, which served as our textbook in Roger Gilbert’s modern poetry seminar at Cornell, back in the late ’80s (I still might have that book on my shelf somewhere). I remember taking great joy in the poem, “Animals are Passing From Our Lives,” with it’s bleak, defiant, somewhat mocking, and unexpected ending: “No. Not this pig.” It’s a phrase I still repeat to myself in certain situations. Similarly, “They Feed They Lion” made an impression, with the driving urgency of its language. But though these earlier works were remarkable in their own right, they barely hinted at what he would later achieve in What Work Is. For me, and many other young male poets, that book was a revelation. It deeply influenced everything I wrote thereafter, as it probably did for the likes of B.F. Fairchild, Joseph Millar, and others who would be hypnotized by the force and muscularity of his verse. Thin, taut, the cascade of lines carried the reader down the page, dragged the reader into a world that was far removed from the effete ivory towers of academia. But though they were powerful, I would not call his poems raw, for they were in fact impeccably engineered. Certainly, they taught me the importance of cadence, and the sense that you could not work on a particular line without considering every line that came before it, and the collective rhythm of the poem. I was also struck by what could only be called a dismissive attitude, a tone that said, “this is important, so forget you, if you can’t relate.” Levine also illustrated the difference between the personal and the confessional, as well as the distinction between honesty and truth; history is subjective, and therefore, so is truth—but the honesty with which we embrace that truth must be incontestable. And of course, the characters themselves, straight out of story by Isaac Babel! Nobody else was writing about such people at the time, with the intimacy that comes from first-hand knowledge and the wisdom that comes from detached regard. His politics were also out of the mainstream. As a young man, he had been an ideological communist, espousing the belief that “property is theft,” and displayed an apparent bond with the anti-fascists in Spain. This, too, influenced my work at the time.

![]() Side note: Shortly after the publication of What Work Is, Levine gave a reading at a small bookstore in LA. I don’t remember now whether he was promoting that book, or the next one, The Simple Truth, but is strange to think now that he was still reading to sparse crowds at such a venue. But though I had devoured the book, I had never seen him in person. So, I was expecting this brooding hulk of a man, a steelworker or truck driver, with a stentorian voice like that of James Earl Jones. Instead, here was this wiry little guy with a whiny little voice. The incongruity was unsettling. It also intrigues me to think of him in the cattle burb of Fresno in California’s central valley, ground zero for the migrant farm-labor industry, about as far as you can get from the grimy confines of Detroit and the hearty eastern European stock that took root there. But perhaps it’s the vast open spaces there (ever redolent of dung and fertilizer) that focused his mind and verse.

Side note: Shortly after the publication of What Work Is, Levine gave a reading at a small bookstore in LA. I don’t remember now whether he was promoting that book, or the next one, The Simple Truth, but is strange to think now that he was still reading to sparse crowds at such a venue. But though I had devoured the book, I had never seen him in person. So, I was expecting this brooding hulk of a man, a steelworker or truck driver, with a stentorian voice like that of James Earl Jones. Instead, here was this wiry little guy with a whiny little voice. The incongruity was unsettling. It also intrigues me to think of him in the cattle burb of Fresno in California’s central valley, ground zero for the migrant farm-labor industry, about as far as you can get from the grimy confines of Detroit and the hearty eastern European stock that took root there. But perhaps it’s the vast open spaces there (ever redolent of dung and fertilizer) that focused his mind and verse.

It’s a shame that I often don’t revisit a poet’s work until I hear that they’ve died. But in this case, I’m looking forward to pulling those books off my shelf and reliving my early joy in discovering them.