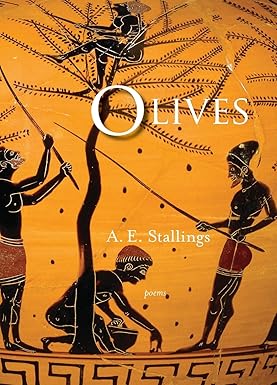

Text and subtext: everything in the work of A. E. Stallings seems to have at least two meanings, or layers of meanings. Her latest collection, Olives, is no exception. Even the title of the book is freighted. Stallings lives in Athens, Greece, named for the goddess Athena, who won the city’s allegiance in a contest with Poseidon. Each gave a gift to the city: Poseidon gave a wellspring (but the water was salty), and Athena gave… an olive tree. The olive, then becomes synonymous the whole Greek drive toward an enlightened civilization. Of course, the olive branch has also come to represent a gesture toward peace and conciliation—equally appropriate in a book that is woven through with scenes or hints of domestic tension.

The book is separated into four sections. The first is entitled “The Argument.” Double meaning again: it is the title of a poem in this section; but it is also an old term for an introduction or explanation of a work. Astute readers may recall Herrick’s “The Argument of His Book.” In any case, this first section contains more than a few actual arguments between people real and imagined. “Recitative” notes, “We cherished each our minor griefs / To keep them warm until the night / When it was time again to fight.” This is followed by “Sublunary,” which begins with a couple “Arguing home through our scant patch of park.” Similarly, “On Visiting a Borrowed Country House in Arcadia” begins, “To leave the city / Always takes a quarrel.” And then, of course, there is this section’s titular poem, “The Argument.” Given all this, it’s hard not detect a sense of domestic strife running through the other poems. “Burned,” which begins, “You cannot unburn what is burned,” becomes more than just a litany of life’s small failures, but a recasting of life’s major regrets—the words you wish you didn’t say, the decisions you wish you hadn’t made. “The Compost Heap” is at once suggestive of a new beginning, but also of buried sentiments that must someday rise again, perhaps in a new, more potent form. “The Dress of One Occasion” is an ode on a wedding dress; but within the context of this first section, it also becomes a requiem for lost innocence, optimism, and naive love. The following sonnet-like poem, “Deus Ex Machina,” also describes the loss of disillusionment, the existential angst of a couple that is past the honeymoon stage. The title refers to a contrived device whereby playwrights who could not compose a suitable denouement would simply cut the gordian knot and have a god descend from the rafters to settle the conflict on stage. In this poem, the two lovers have reached an impasse, a critical stage from which they see no exit, having assumed the roles that history and society have written for them. Intriguingly, the poem ends with no final punctuation, no period or exclamation point, suggesting, of course, that the requisite god is not forthcoming, and there will be no miraculous rescue.

The language in this section—indeed, throughout the book—is impeccably precise. Here’s a quatrain from “The Compost Heap”:

And held its ground against the snow,

The barrow of the buried year,

The swelling that spring stirred below.

Perhaps not everyone knows what a barrow is (but Tolkien fans might recall the barrow downs), but it’s a rich and apt description of the compost heap. I love the description in “Telephonophobia” (fear of the telephone) as well. To justify such a fear, the poem notes that “We keep it on a leash” (though I wonder: will such a reference soon become apocryphal, as we make the final leap to cordless technology?) Furthermore, when the speaker lifts up the receiver, “Old anger pours like poison in my ear,” a phrase that can’t help summon an image of Hamlet’s father—which is all the more appropriate, if the true fear of phones is the news they bring of the death of someone near.

The next section, “The Extinction of Silence,” is a bit more outwardly focused, and speaks to or about specific people (many of whom are deceased). The standout poem for me in this section is “The Cenotaph,” which describes a visit to the first cemetery in Greece (where Schliemann, archaeologist of windy Troy, is buried). The speaker encounters both the living and the dead, and—most movingly—a small child who is both, that is, a statue that seems alive and playful. I love the phrase, “the rude democracy of bone.” Ultimately, the speaker comes to realize, “It was the grave of nobody I sought,” which on the one hand is the everyman, not unlike the tomb of the unknown soldier, but on the other hand, the speaker’s own grave, which is of course not yet there. In such a statement, the speaker on some level acknowledges the nobody that everybody is destined to become. The speaker also notes “the token of undying love / Some twenty years ago” that has become “garish” over time. In the final couplet, the speaker remarks that she “Wandered between two dates,” the birth date and death date inscribed on every stone. That’s one of those lines that stops you in your tracks, subtle yet overwhelmingly potent.

The next section, “The Extinction of Silence,” is a bit more outwardly focused, and speaks to or about specific people (many of whom are deceased). The standout poem for me in this section is “The Cenotaph,” which describes a visit to the first cemetery in Greece (where Schliemann, archaeologist of windy Troy, is buried). The speaker encounters both the living and the dead, and—most movingly—a small child who is both, that is, a statue that seems alive and playful. I love the phrase, “the rude democracy of bone.” Ultimately, the speaker comes to realize, “It was the grave of nobody I sought,” which on the one hand is the everyman, not unlike the tomb of the unknown soldier, but on the other hand, the speaker’s own grave, which is of course not yet there. In such a statement, the speaker on some level acknowledges the nobody that everybody is destined to become. The speaker also notes “the token of undying love / Some twenty years ago” that has become “garish” over time. In the final couplet, the speaker remarks that she “Wandered between two dates,” the birth date and death date inscribed on every stone. That’s one of those lines that stops you in your tracks, subtle yet overwhelmingly potent.

The third section, “Three Poems for Psyche,” is brief but packed. The three poems in this section ease the reader into a central theme of the final section—that is, motherhood—while recasting themes of domestic strife and the impassivity of time introduced in the first two. The first poem is remarkable, formally. It is essentially a palindrome, with each line of the first stanza repeated in the second—in reverse. In this, it bears some similarity with Natasha Trethewey’s Orpheus poem (see earlier post). This sequence does not focus so much on the main part of the Psyche story (her encounters with Cupid), but rather, on what happens next. For the Psyche in these poems is pregnant (with sensual bliss, according to the allegory). And, to appease Venus, she must descend into the underworld to retrieve some beauty from Persephone. Of course, the only beauty the goddess knows is the ageless beauty of the grave. And Persephone is not the young naive girl who first entered Hades, but is notably wiser, perhaps jaded (though of course, no older).

The final section, “Fairy Tale Logic,” strikes a somewhat different tone—at times exasperated, at times effulgent—which is not surprising, given that many of these poems focus on childrearing. The title and poem of the same name reflect on the impossible but completely accepted premises of fairy tales and nursery rhymes (and calls to mind Nick Flynn’s “Cartoon Physics”). The title poem starts out on a whimsical note, “Gather the chin hairs form a man-eating goat,” but ends with a devastating imperative: “Marry a monster. Hand over your firstborn son.” There is some genuine rage and despair underlying these lines, particularly in light of the book’s first section. The double-entendres in “Two Nursery Rhymes: Lullaby and Rebuttal” are amusing and incisive. I love the way a figure of expression (two figures, actually) take on practical significance in the first lines: “For crying out loud, / It’s only spilt milk.” Same thing for the second stanza, told from the baby’s perspective, which begins, “I have drunk all I can of you” (and I hear an echo of “Drink to me only with thine eyes” in that line). A few lines later, it’s “the sorrow you call teeth / That gnaws at me.” Again, fabulous turns of phrase and double meanings.

I am particularly interested in poetry that does things that prose simply cannot do. Partly that’s why I am drawn to form. But I’m even more intrigued when the form itself tells a story. Such is that case with a particularly masterful poem from this section, “Alice in the Looking Glass.” Looking at the line endings, the form is not immediately apparent. They begin and end on the same word, “time.” But in between, the end words are not rhymes but opposites. So, “there” in the second line becomes “here” in the penultimate, “left” in the third line becomes “right” in the third from the bottom. In this way, the form is physically recreating the experience of gazing in a mirror. Even without the form, the poem is a poignant reflection of the speaker’s state of mind in thinking, presumably, about her deceased mother—an event that is perhaps occasioned by looking in the mirror and seeing the mother’s face in her own.

I read a review somewhere that chided Stallings for including the poem “The Mother’s Loathing of Balloons” in this collection because the reviewer felt it was in someway derivative of Sylvia Plath. I can’t imagine, though, Plath weaving in a reference to Aeolus and his bag of winds that famously send Odysseus back to his misery even in sight of his homeland (though I suppose she might begin a poem with “I hate you”). What’s more, I’d venture to guess that Stallings is not well versed in Plath, who holds very little allure for formalist poets of a certain age (a group in which I’d place myself). Indeed, a reviewer of my first book faulted it because it failed some strained comparison with Plath, whom I had not read since I was sixteen. So, let me just spell it out for all future reviewers: serious poets don’t read Plath. At least not past adolescence.

One final thing for which I must commend A. E. Stallings: her apparent disdain for book blurbs. Her second book had an “antiblurb” poem on the back, and this one also includes a poem on the back cover instead of the requisite treacle, which, ultimately, only goes to show how well connected you are, or what sort of clout your publisher has. I think it’s a good idea. Personally, I am not swayed by blurbs from poets that I admire, but I am definitely dissuaded from buying a book that carries blurbs from poets that I don’t like.