George Bradley: Terms to be Met

I’m not dead—just busy. But I happened to steal a few minutes this past weekend to pop into a used bookstore (that is, the books are used. I presume the bookstore is, too) where I chanced upon a copy of George Bradley’s Terms to Be Met, which won the 1986 Yale Younger Poets Series, selected by James Merrill. I know I’ve encountered Bradley’s work in the past. Certainly, the titles of some of his books ring a bell—The Fire Fetched Down and Of the Knowledge of Good and Evil—but I don’t recall any specific poems. My loss, because these are wonderful poems. In some ways, they are emblematic of the mid 80s, combining something of a world-weariness with a wry wit. They also bridge the gap between the confessional and formalist modes, with an easy, colloquial delivery that often masks an astute structural underpinning. The first poem, “In Suspense,” is a fine example. The poem is occasioned by a trip across the Verrazano bridge. The language itself is soaring—no aversion to multisyllabic words here—though the tone conveys a slightly bemused self-effacement:

To much besides a perception of ourselves

As puny and audacious, caught in a monumental

Undertaking…

The form is itself the “monumental undertaking,” structurally symmetrical as the bridge itself. The end-words of the first 13 lines become the end-words for the final 13, though played in reverse. The middle (14th) line ends in the word “summit.” I’ve discussed poems like this before (and have even written some), but this is among the earliest instances I’ve encountered. In this way, Bradley is somewhat of a harbinger for the later school of “neo-formalists,” who did not simply revive traditional forms but sought (seek?) to create new forms, to bridge the river between medium and message. Bradley even dapples in concrete poetry. “Life as We Know It” is shaped like a circle on the page—or more specifically, a sphere, which comes to represent not only our planet but the ideal or most efficient form of matter. “The Old Way of Telling Time” assumes the shape of an hourglass. That in itself is not remarkable, but the genius in this poem lies at it’s very heart, as the last word of the top part of the hourglass is broken to become also the first word of the bottom part. But wait, it gets better: the word is hyphenated—and the hyphen occupies the midpoint of the hourglass. Wow.

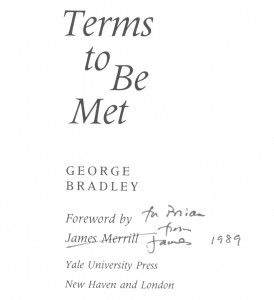

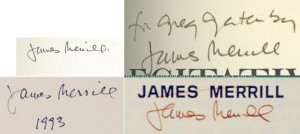

And speaking of Merrill, I was intrigued by an inscription on the title page, which seems to read, “To Priam, from James.” Attached, as it is, to the “Foreword by James Merrill” type, I can’t help wondering whether I have stumbled across a book signed by Merrill. In comparing it to other signatures, there is a definite similarity, but unfortunately, no last name. I’ll have to consult an expert. Regardless, I’m delighted to have chanced upon Terms to Be Met, which is definitely a book to be read. Again and again.