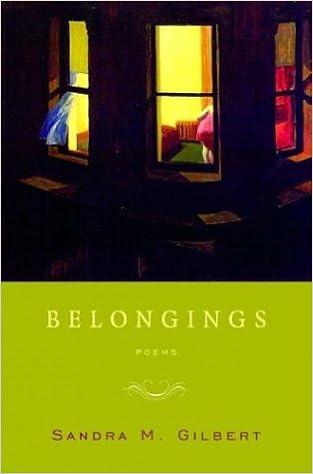

Sandra Gilbert: Belongings

Welcome 2021! Ring out the old, ring in the new!

So as I was browsing through the “G” section of my poetry shelf (see previous post), I came across a book that I hadn’t picked up in several years, Sandra Gilbert’s Belongings. Gilbert is perhaps best known for her early feminist theory, particularly her collaborations with Susan Gubar. While not questioning the value of that work, I think it is unfortunate that she has not received broader recognition as a poet. Her work is at times subtle, forceful, intimate, and challenging. It compresses serious intellectual discourse into engaging, superbly crafted verse.

I am of course impressed by her formal acumen, but I find her personal narrative equally compelling. Gilbert comes from Italian ancestry—specifically, Sicilian—a heritage that I share. In fact, crazy synchronicity: her book of collected poems is called Kissing the Bread. The title poem describes her mother or grandmother kissing the stale bread before throwing it away. So, one day, I’m driving with my parents. We may have been on our way to visit my grandmother’s grave, or perhaps it was around the anniversary of her death. And out of nowhere, my father says, “Remember how she always used to kiss the heel of the bread before throwing it away?” I was stunned. I guess it just goes to show how even seemingly unique personal memories can have much greater resonance than we imagine.

The title poem in Belongings is a traditional sonnet sequence that recounts her mother’s decline into senility, dementia, and ultimately, death. She is torn between the world of the living and the world of the dead, of the physical and the spiritual. Delusional, she is visited by the ghosts of her childhood—and apparently is at ease conversing with her deceased relatives. But she is also haunted by more malign spirits—the uncouth “others” who are plotting to steal her stuff. In fact, she clings to her belongings as a way of clinging to the world and her identity. She has come to define herself, and the fact of her existence, by her possessions. The overall poem comprises 14 sections, making it something of a meta-sonnet. They are linked not only thematically, but through the poetic device of repeating the last line of one sonnet as the first line of the next (I tried reading the first lines as a single poem, but it didn’t work). There’s also an interesting lack of punctuation and use of extra spaces to serve as partial caesuras within each line. It’s not intrusive or gaudy—just slightly edgy in a poem like this. The lack of punctuation is common throughout the book—perhaps in keeping with the poetic fashion of the day—along with the device of using the first line as the title (a practice I never quite agreed with).

The main figure in “Belongings” appears in other poems, as does the memory of Gilbert’s husband, who evidently suffered an untimely and unexpected death. In fact, Gilbert is at her best in the elegiac mode, lamenting—no, contemplating—both family members who have gone and the fleeting moments in her life that exist now only in memory. Another sonnet sequence bookends the collection, “A Year and a Day,” which dedicates a poem for every month, followed by “February 11, 2003,” presumably the anniversary of her husband’s death (a mere three days before Valentine’s day). This poem echoes the same dedication found in the prologue: “in memory of E.L.G.” It is a meditation both on poetry and grief—the formal structures that prop us up, and the heavy, seemingly futile, search for meaning. It ends with the lines,

in the empty, there isn’t room to turn around.

I’m noticing now that I did not pull many quotes from the collection. That’s because there are too many great lines to choose from.

I should mention that in my senior year at Cornell, Sandra’s son Roger came to teach, fresh out of grad school. I was having trouble finding someone to direct my Independent Study and senior thesis, and was immensely fortunate that Roger accepted the task. I suspect he was happy to find someone who was more interested in his literary theory than his mother’s. He proved to be a great mentor and astute reader of poetry (even my self-absorbed college verse). Years later, I chanced to meet Sandra at the annual SLO Poetry Fest (and I recall hearing selections from this book, which was not yet published). I mentioned my connection to her son. We only spoke for a minute or two, but in that brief time, she made me feel like part of her extended family.

Her poems do the same thing, even for those with no Italian heritage to draw upon.